We've had a recent rash of vagrants around the Great Lakes; including (but not limited to) White-winged Dove, Common Ground-Dove, Ash-throated Flycatcher, Golden-crowned Sparrow, Neotropic Cormorant, Townsend Solitaires etc.

Oh, and HEPATIC TANAGER

The weather - hasn't been the typical storm environment highlighted by birders for vagrancy - such as large extratropical cyclones. It was rather "boring" on the storm front, but I think I'm starting to get a handle on a different weather event that brings vagrants in the fall (maybe spring too, but for now - let's look at fall). It is:

ZONAL FLOW

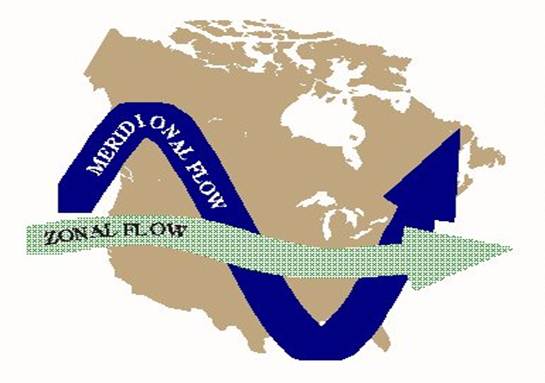

Per wikipedia: Zonal flow is a meteorological term regarding atmospheric circulation following a general flow pattern along latitudinal lines, as opposed to meridional flow along longitudinal lines. Zonal, in the context of physics, connotes a tendency of flux to conform to a pattern parallel to the equator of a sphere. Generally, zonal flow of the atmosphere brings a temperature contrast along the Earth's longitude. Extratropical cyclones in this environment tend to be weaker, moving faster and producing relatively little impact on local weather.

Here is a rough graphic showing how air (jet stream) and (smaller) storms would be traveling in this type of scenario:

I first noticed this phenomenon when studying a great vagrancy event in fall 2009, but first I'll show the recent weather maps.

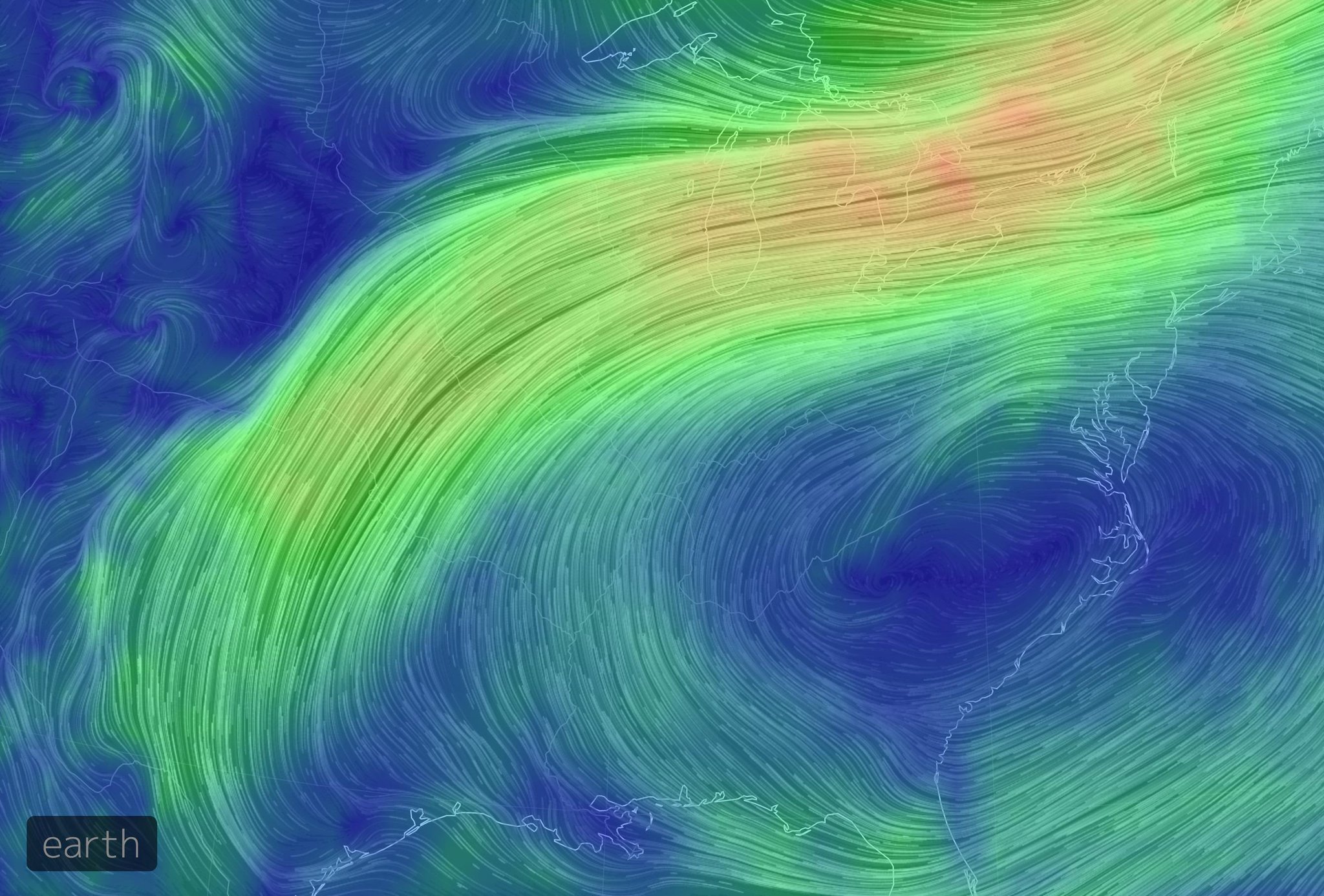

Weather map from Tuesday (Hepatic day). Note the lack of strong storms - or much of anything really... (Not considering the strong storm over Hudson Bay, just off screen). But what did the 850mb (~1500m up off the surface) wind map look like?

Long distance winds flowing from Texas into the Great Lakes, moving INTO the zonal flow and around the outside edge of a strong centre of high pressure over the eastern USA. I've marked up a few maps to show this:

Map interp (same as above) Yellow line indicating the (nearly) zonal flow of the jet. Green line is showing the direction of airflow that I would expect (just by looking at the surface map).

Real-life observations of 850mb winds (1500m up) and the centre of high pressure drawn on.

One of my best "case studies" for Great Lakes vagrancy is early November 2009 - when we had the following birds appear in Ontario: Ash-throated Flycatcher (Pelee), Sulphur-bellied Flycatcher (Oakville) and Phainopepla (Brampton). Some "other" things found around the same time included Lark Sparrow, Summer Tanager and Western Kingbird. So what was the weather like?

The ATFL and SBFL were both found on Nov 6th, with the others coming afterwards. I am inclined to believe that birds (like the PHAI) "arrived" at the same time, it just took a few days for it to be found. So - I went straight for the maps overnight from Nov 5th - 6th:

See the similarities? I've marked it up:

Once again, the yellow line shows the "rough" zonal flow, and the green lines show the flow of air... The little "warm front" passing over southern Ontario may have helped concentrate birds in S. Ontario more than the recent event which has them spread out over a larger area.

Looking into this type of weather/bird event is quite interesting to me, but also raises many questions or unexpected observations:

- the Hepatic Tanager "overshot" the area I thought would be the "hot zone". Why?

- why are these birds flying north on these S or SW winds? Why don't they just stay put?

- are there any mechanisms at play that would help one predict where the best places are? (eg, why the Hepatic showed up at WPBO)

- or is this type of setup a poor one for predictable landing spots (eg,/ 2009's Phainopepla in Brampton).

- what happens to these birds? (This is what gives me a headache when trying to correlate birds to weather). If a Scott's Oriole is found on a CBC this Dec - is there a chance it actually arrived in ON during this recent storm?)

- I strongly feel that these vagrants are undertaking a single, exceptional flight over LONG distances to reach our shores.

- the mechanism for predicting "good" vagrancy weather remains unobstructed, LONG DISTANCE winds; which allows them to undertake these huge flights.

Models are hinting at some unusual weather next week - lots of moisture from the south and potential for big winds and a strong extratropical low. Not the same as this, but exciting it its own way!

Brandon, I had noticed "Cave Swallow weather" - long distance winds from the US/Mexican border through the Great Lakes - last week, followed by a decent cold front. Despite the slightly early date (by about a week), there were a couple Cave Swallows in CT and an Ash-throated Fly in NJ. That long SW "fetch" at this time of year seems to consistently result in western/central vagrants to the northeast (anecdotally anyway...not sure if there's any data to support that), especially those two species.

ReplyDeleteCave Swallow seems like it might be an especially good indicator species for vagrant searchers because they can be widespread when present and are easy to see relative to skulking species. I wonder if that is actually the case, or if it just seems that way.

I think it's a mixed bag personally (using CASW as an indicator) I think a CASW weather blog post is in order. I'd say this recent setup is 1 of 3 "styles" that have brought them N before. I am also not as familiar with the exceptional situations that can bring vagrants to the E coast compared to the Great Lakes!

Delete"why are these birds flying north on these S or SW winds? Why don't they just stay put?"

ReplyDeleteIf these migrants have their internal orientation settings switched 180 degrees, then a SW flow would be in the direction that they would tend to travel.

Enjoy reading your analysis; have you read the Migration and Vagrancy in Birds chapter from "Rare Birds of North America"?

Will this next system bring any Cave Swallows?

Alfred Adamo

I have the book but I haven't read it yet... I need to do that!

DeleteAlso - if the birds had their orientation switched, then they should fly N on all south winds, moving N in stages (like spring migration) whereas my personal thoughts are that they don't behave that way (a single massive jump instead). CASW seem to, but not Hepatic Tanagers etc. Perhaps I'll do a few more blog posts on the subject at some point!

- as for this storm, in the Great Lakes - I do not expect any NEW CASW to arrive. (Note: need CASW weather blog post) - BUT, there have been CASW already on the E coast at one at WPBO, so there should be some around to be found... Point Pelee on the next N wind would be my best bet, but I wouldn't have high hopes.

Glad you like the weather talk!

Brandon - Agree that these birds fly great distances in one flight; this is the reason why many vagrants feed so voraciously when they arrive. Agree with your Tyrannus ID after seeing some photos but still need to consult Pyle. Anyway, how could a bird so worn and missing flight feathers get this far?

ReplyDeleteDave Bell had a great suggestion in that EAKI molt on the wintering grounds, so somehow it was blown back N after migrating and beginning it's molt... My thoughts (before seeing his comments) were that it never left, and had some sort of feather issue (hence why it is still here in late Oct). I know a pretty ratty FTFL arrived at Long Point a few years ago in April, so it's not out of the question, but....

Delete